Grand Tour by Hearse

I was one of six architectural students who determined that they would enjoy a Grand Tour to Italy before their final year and they would no longer be together. In 1958 we were students at the Birmingham School of Architecture, then part of the College of Arts and Crafts in Margaret Street, Birmingham (UK).

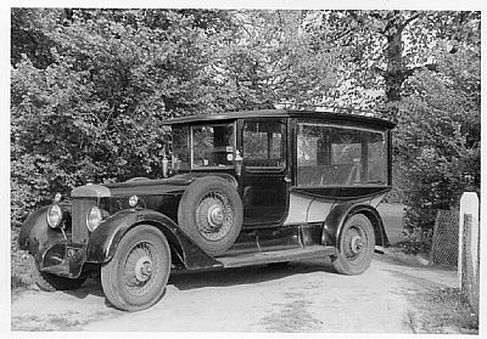

We needed an old vehicle for the journey, perhaps a former ambulance or an old army truck. I saw a hearse in a car mart at Aston, but, to our disappointment, it had been sold. Then we found another hearse (registration OM 1015) and bought it in February 1958 for £40 from a Birmingham undertaker (see picture below). It had been in use up to six months beforehand and the undertaker was rather sorry to see it go; he urged us to look after it.

We needed an old vehicle for the journey, perhaps a former ambulance or an old army truck. I saw a hearse in a car mart at Aston, but, to our disappointment, it had been sold. Then we found another hearse (registration OM 1015) and bought it in February 1958 for £40 from a Birmingham undertaker (see picture below). It had been in use up to six months beforehand and the undertaker was rather sorry to see it go; he urged us to look after it.

The ornate body was mounted on the chassis of a 1924 Daimler van powered by a massive 30 bhp (22.5 kW) sleeve-valve engine and the whole vehicle weighed 2.5 tons (2540 kg). Such engines were used in some prewar sports cars, the Willys-Knight car and light truck and saw substantial use in aircraft engines of the 1940s, such as the Napier Sabre, the Bristol Hercules and the Centaurus. They were very quiet engines (when new), which is why one came to be used for a hearse. They subsequently fell from use due to advances in poppet-valve technology and to their tendency to burn considerable amounts of lubricating oil or to seize due to lack of it. We certainly found it heavy on oil. The petrol consumption was about 11 mpg (25.6 l/100 km), but the oil consumption was only about ten times better. We had to carry a barrel of oil on the running boards to keep topping up and we left a trail of smoke behind us. Most evenings on the tour, we had to call at local garages to ask for used sump oil to replenish our supply (sometime we got that free). Nevertheless, the engine was so solidly built that there was little danger of it suffering a structural failure.

We removed the coffin platform with its silver candelabra (it was abandoned at Ocker Hill power station, where my father was then the superintendent, and replaced it with old seat squabs so that four could sit in the back; two sitting in the driving cab. We could climb through a hatch between the cab and the rear. We also did some repainting and fitted cane sunshades to the glass side windows. Two were to sleep in the vehicle and the others in tents.

But where to store it until we set off? For most of the time before the Tour and for a while after it, the hearse stood in the driveway of my parents’ house in Sutton Coldfield This caused comment by and amusement to passers by and some embarrassment to my parents. For several months before the Tour, various fellow students used the vehicle for excursions, including an architectural conference at Attingham Park near Shrewsbury. Without power steering or brakes and with no synchromesh on the gearbox, driving it was a challenge. I found gear changing particularly difficult, but as the mechanic, I saw to it that everything worked as it should and arranged insurance.

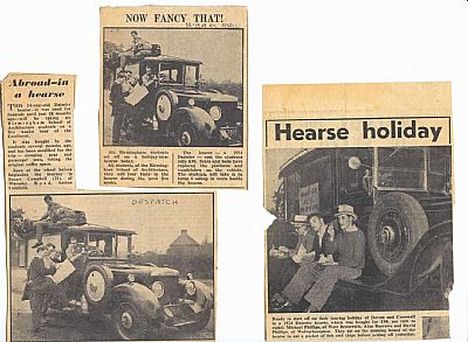

Somehow the local press heard about the trip and carried stories about it. They even turned up to see us off (see press items below).

We removed the coffin platform with its silver candelabra (it was abandoned at Ocker Hill power station, where my father was then the superintendent, and replaced it with old seat squabs so that four could sit in the back; two sitting in the driving cab. We could climb through a hatch between the cab and the rear. We also did some repainting and fitted cane sunshades to the glass side windows. Two were to sleep in the vehicle and the others in tents.

But where to store it until we set off? For most of the time before the Tour and for a while after it, the hearse stood in the driveway of my parents’ house in Sutton Coldfield This caused comment by and amusement to passers by and some embarrassment to my parents. For several months before the Tour, various fellow students used the vehicle for excursions, including an architectural conference at Attingham Park near Shrewsbury. Without power steering or brakes and with no synchromesh on the gearbox, driving it was a challenge. I found gear changing particularly difficult, but as the mechanic, I saw to it that everything worked as it should and arranged insurance.

Somehow the local press heard about the trip and carried stories about it. They even turned up to see us off (see press items below).

After setting off from Sutton Coldfield on 9 August 1958, we reached Dover two days later and crossed the channel, when I think we scraped the roof of the ferry’s car deck. Our first stop was Expo 58, also known as the Brussels World’s Fair. The Fair, the first major World's Fair after World War II, was symbolized by André Waterkeyn’s Atomium, a giant model of the unit cell of an iron crystal, magnified 165 billion times. Although renovated, it still stands today (see http://www.atomium.be/).

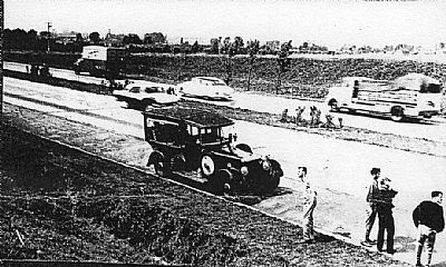

From Brussels, we headed west through Luxembourg into Germany. There we caused congestion on the German motorways (see picture below).

From Brussels, we headed west through Luxembourg into Germany. There we caused congestion on the German motorways (see picture below).

There being few old vehicles left in Germany, the sight of our curious vehicle caused drivers to slow down to have a look at. They would even drive alongside, taking pictures and causing traffic to build up behind. When we stopped at a campsite in Germany, we would be unable to settle down for an hour or so because of the constant questions about the vehicle, which Germans mistook for a Daimler-Benz (in fact Daimler-Benz AG was not formed until two years after the hearse was built). ‘No’, we had to explain, ‘this is an English Daimler’ (the Daimler Motor Company was founded in 1896 and based in Coventry). Germans found that hard to understand. This interest resulted in us appearing in German newspapers. See the picture of us surrounded by curious campers at a campsite at Idstein, near Frankfurt.

On we went: through Aachen, Cologne, Deardorf, Karlsruhe, Stuttgart, Ulm, and into Austria via Munich, Salzburg and Innsbruck. We then had to cross the Alps. We did this by climbing the Brenner Pass, at 1370 m the lowest and easiest of the Alpine passes. Even so, the hearse had a struggle and, at one point, we all got out except for the driver, to lighten the load. We worried that it might not make it over the pass, but it did—just.

We were then into Italy, via Trento, Verona, Vicenza, Padua, and Mestre, arriving at a lido near Venice on 24 August. We eventually reached Venice itself via a bus and a ferry that dropped us at St Mark’s Square. We had originally planned to reach Rome, but that was a journey too far.

On 28 August we left the lido and set off back home. However, after the difficulty experienced getting over the Brenner Pass, we decided to avoid climbing the Alps by taking the hearse on the railway through the Simplon Tunnel.

So we took a different route back, via Padua, Vicenza, Verona and Brescia, stopping off in Milan to see the then recently completed Pirelli Tower designed by Gio Ponti, assisted by Pier Luigi Nervi and Arturo Danusson. It is the tallest building in Milan and was until recently the tallest building in Italy (see picture).

In fact, the Simplon Tunnel was blocked by a landslide and, in any case, it seems not to have been able to carry vehicles. So, after a very steep climb, we travelled on the railway through the St Gotthard Tunnel on 1 September (see picture). The 15 km tunnel from Airolo to Wassen was opened in 1882.From Wassen in Switzerland, we headed north and, after Luzern, we crossed into France at Basle. Then onto Belfort, from where we visited Le Corbusier’s famous chapel: Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp (see http://www.demel.net/fs-ronchamp.html).

Afterwards he headed west to Versailles and north up to Calais, from where we crossed by ferry back to the UK.We arrived back in the Birmingham on 8 September, after a Grand Tour of thirty days. Apart from the loss of two tyres, the hearse had performed magnificently. We carried two spare wheels of an unusual size and with rare tyres. Another burst tyre and we would have been stranded. We had covered 2434 miles (3894 km}, consumed 1005 litres of petrol and 91.5 litres of oil. Overall, we probably spent £30 each, about £500 today.

We eventually sold the hearse for £20 to a youth club in Maidenhead. Did the tour enrich our appreciation of architecture? Somewhat, but we did get good experience of foreign travel.

On we went: through Aachen, Cologne, Deardorf, Karlsruhe, Stuttgart, Ulm, and into Austria via Munich, Salzburg and Innsbruck. We then had to cross the Alps. We did this by climbing the Brenner Pass, at 1370 m the lowest and easiest of the Alpine passes. Even so, the hearse had a struggle and, at one point, we all got out except for the driver, to lighten the load. We worried that it might not make it over the pass, but it did—just.

We were then into Italy, via Trento, Verona, Vicenza, Padua, and Mestre, arriving at a lido near Venice on 24 August. We eventually reached Venice itself via a bus and a ferry that dropped us at St Mark’s Square. We had originally planned to reach Rome, but that was a journey too far.

On 28 August we left the lido and set off back home. However, after the difficulty experienced getting over the Brenner Pass, we decided to avoid climbing the Alps by taking the hearse on the railway through the Simplon Tunnel.

So we took a different route back, via Padua, Vicenza, Verona and Brescia, stopping off in Milan to see the then recently completed Pirelli Tower designed by Gio Ponti, assisted by Pier Luigi Nervi and Arturo Danusson. It is the tallest building in Milan and was until recently the tallest building in Italy (see picture).

In fact, the Simplon Tunnel was blocked by a landslide and, in any case, it seems not to have been able to carry vehicles. So, after a very steep climb, we travelled on the railway through the St Gotthard Tunnel on 1 September (see picture). The 15 km tunnel from Airolo to Wassen was opened in 1882.From Wassen in Switzerland, we headed north and, after Luzern, we crossed into France at Basle. Then onto Belfort, from where we visited Le Corbusier’s famous chapel: Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp (see http://www.demel.net/fs-ronchamp.html).

Afterwards he headed west to Versailles and north up to Calais, from where we crossed by ferry back to the UK.We arrived back in the Birmingham on 8 September, after a Grand Tour of thirty days. Apart from the loss of two tyres, the hearse had performed magnificently. We carried two spare wheels of an unusual size and with rare tyres. Another burst tyre and we would have been stranded. We had covered 2434 miles (3894 km}, consumed 1005 litres of petrol and 91.5 litres of oil. Overall, we probably spent £30 each, about £500 today.

We eventually sold the hearse for £20 to a youth club in Maidenhead. Did the tour enrich our appreciation of architecture? Somewhat, but we did get good experience of foreign travel.