The Arnold Report Explained

(This is an edited and unreferenced version of a chapter in my book The UFO Mystery Solved).

The first flying saucers

Most writers on UFOs seem to believe that it is not known what it was that Kenneth Arnold saw on 24 June 1947. It is certainly true that the incident has never been explained satisfactorily. Yet if we cannot explain this seminal case, we can hardly claim to have made much progress in explaining UFO reports.

The pilot's tale

Arnold used a light aircraft to sell fire fighting equipment over five western states of the USA and, by 1947, he had over 1000 hours flying experience. In January of that year, he bought a new Callair monoplane. On 24 June 1947 he was flying this aircraft from Chehalis to Yakima (Washington), but he took an extra hour to search for a crashed aircraft. Eventually he abandoned the search over a small town called Mineral, and set course at a height of 2800 m for Yakima in the east.

After setting the autopilot, he was able to look about him. The air was crystal clear, with visibility up to 80 km (at least). He noticed a DC4 to his left rear at about 25 km and 4200 m high, but after two or three minutes he was startled by a bright flash to his left, to the north of Mt. Ranier. There he saw a chain of nine peculiar 'aircraft' flying (apparently) from north to south. He estimated that their course was 170º and that they were at approximately his flight level. They were flying in echelon formation but (contrary to USAF practice) with the leader highest, and as if they were all linked together (that is, they all moved at exactly the same speed). He observed that there was a gap between the first four objects and the last five.

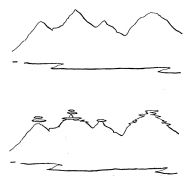

Arnold was bothered by the fact that he could see no tail fins on the craft; no aircraft could fly without this distinctive feature. They appeared merely as a thin black lens shape, but every few seconds two or three of them would produce a brilliant blue white flash which Arnold interpreted as sunlight reflecting off wings as the craft dipped them (although he could see no wings). When flashing, the objects appeared to be completely round (see figure 1), although one was darker and a different shape. It was Arnold's attempt to describe this flashing that led to the objects being described by the press as 'flying saucers'. He likened the behaviour to powerboats at speed or saucers skimmed across water, but this does not appear to have been intended to be taken too literally. His simile was intended to illustrate the irregularity of the flashes. He did not allege that the objects made any vertical movements as observed in boats or saucers on water.

After setting the autopilot, he was able to look about him. The air was crystal clear, with visibility up to 80 km (at least). He noticed a DC4 to his left rear at about 25 km and 4200 m high, but after two or three minutes he was startled by a bright flash to his left, to the north of Mt. Ranier. There he saw a chain of nine peculiar 'aircraft' flying (apparently) from north to south. He estimated that their course was 170º and that they were at approximately his flight level. They were flying in echelon formation but (contrary to USAF practice) with the leader highest, and as if they were all linked together (that is, they all moved at exactly the same speed). He observed that there was a gap between the first four objects and the last five.

Arnold was bothered by the fact that he could see no tail fins on the craft; no aircraft could fly without this distinctive feature. They appeared merely as a thin black lens shape, but every few seconds two or three of them would produce a brilliant blue white flash which Arnold interpreted as sunlight reflecting off wings as the craft dipped them (although he could see no wings). When flashing, the objects appeared to be completely round (see figure 1), although one was darker and a different shape. It was Arnold's attempt to describe this flashing that led to the objects being described by the press as 'flying saucers'. He likened the behaviour to powerboats at speed or saucers skimmed across water, but this does not appear to have been intended to be taken too literally. His simile was intended to illustrate the irregularity of the flashes. He did not allege that the objects made any vertical movements as observed in boats or saucers on water.

For a time, the objects disappeared behind Mt. Ranier, but it was just about 1500L (2300Z) when the first one emerged and he realized that he could time them and ascertain their speed. He was amazed that they were flying so close to the mountain tops; they seemed to be flying down the ridge of a mountain range. He estimated that the objects, almost at right angles to his course, were 30 to 40 km away.

He was flying towards a ridge, the length of which he could measure because it had marker peaks, one at each end. Consequently he resolved to time the objects as they passed this ridge. From the time, and the distance between the peaks, he could calculate their speed (assuming he knew their distance). He found that the last object in the chain took 102 s to pass from one peak to the other; he also noticed that, as the first object reached the 'south' peak, the last one was passing the 'north' peak. Later he determined that the peaks were 8 km apart and therefore that the chain of objects was at least that long.

He estimated that he observed the objects for 2½ to 3 minutes, and claimed that, by the time the objects reached Mt. Adams, they were out of his range of vision. For a while he continued to search, but then he made for Yakima, where he reported what he had seen. By the time he reached Pendleton in Oregon, the news media caught up with him and the 'flying saucer' myth was born.

He was flying towards a ridge, the length of which he could measure because it had marker peaks, one at each end. Consequently he resolved to time the objects as they passed this ridge. From the time, and the distance between the peaks, he could calculate their speed (assuming he knew their distance). He found that the last object in the chain took 102 s to pass from one peak to the other; he also noticed that, as the first object reached the 'south' peak, the last one was passing the 'north' peak. Later he determined that the peaks were 8 km apart and therefore that the chain of objects was at least that long.

He estimated that he observed the objects for 2½ to 3 minutes, and claimed that, by the time the objects reached Mt. Adams, they were out of his range of vision. For a while he continued to search, but then he made for Yakima, where he reported what he had seen. By the time he reached Pendleton in Oregon, the news media caught up with him and the 'flying saucer' myth was born.

Explanations

There have been many explanations. At the time, Arnold thought that the objects were jet aircraft, as did Hynek in his report to Blue Book. It was also suggested that the objects were guided missiles from Moses Lake, 112 km to the north east of Yakima. It has even been suggested that Arnold saw several small plastic balloons. Philip J Klass has reported with approval a suggestion by science writer Keay Davidson that Arnold saw 'glowing meteor-fireball fragments'.

Donald Menzel made several suggestions, but different ones at different times. His first idea was that the objects were either snow ballooning (sic) up from the top of ridges or sunlight reflecting off sharp layers of haze or dust. Later he suggested that Arnold had seen mirages of mountain peaks or, less likely, orographic clouds. Finally he tentatively suggested that the cause was drops of rain on the window. It is reported that the USAF concluded that the objects were mirages, but there has been no elaboration or confirmation of this hypothesis. Arnold formed the impression that the USAF knew what the objects were, and that they had good photographs of them. By mid summer of 1947, he publicized this erroneous impression in magazine articles which gained wide attention. This fostered the 'government conspiracy' myth. The fact that the two officers who visited him were later killed in an airplane crash while investigating another report fuelled further rumours. Menzel's conclusion was that, because there is 'no grist for analysis other than his report', we shall never know what Arnold saw. I shall show that there is 'grist for analysis' and that by grinding it we can fully explain the incident.

Donald Menzel made several suggestions, but different ones at different times. His first idea was that the objects were either snow ballooning (sic) up from the top of ridges or sunlight reflecting off sharp layers of haze or dust. Later he suggested that Arnold had seen mirages of mountain peaks or, less likely, orographic clouds. Finally he tentatively suggested that the cause was drops of rain on the window. It is reported that the USAF concluded that the objects were mirages, but there has been no elaboration or confirmation of this hypothesis. Arnold formed the impression that the USAF knew what the objects were, and that they had good photographs of them. By mid summer of 1947, he publicized this erroneous impression in magazine articles which gained wide attention. This fostered the 'government conspiracy' myth. The fact that the two officers who visited him were later killed in an airplane crash while investigating another report fuelled further rumours. Menzel's conclusion was that, because there is 'no grist for analysis other than his report', we shall never know what Arnold saw. I shall show that there is 'grist for analysis' and that by grinding it we can fully explain the incident.

Analysis of Arnold's account

In his report to Blue Book, Hynek drew attention to an inconsistency and an error in Arnold's account. The latter's estimate of the size of the objects was not compatible with his estimate of distance (given an assumption about the limit of resolution of the eye) and he had wrongly calculated the speed of the objects from the distance and time given. Hynek's criticism was based on the fact that if the limit of resolution of the eye is taken as 3 arc minutes (0.05º), then objects 40 km away would have to be a minimum of 30 m thick (and 600 m long if they were twenty times longer than they were thick). In fact the limit of resolution is usually taken as 1 arc minute (0.016º) and Arnold's sketch shows the objects only about ten times longer than they are thick. It seems that Hynek later retracted these conclusions. However Hynek did not point out (and perhaps did not realize) that Arnold's account of his timing observation is also inconsistent.

Arnold stated that he had 'two definite points' by which he could time the objects. Later he explained that the two points were the northern and southern crests of a ridge which lay between Mt. Ranier and Mt. Adams and towards which he was flying. On later measurement he found that the two crests (he later called them 'mountains') were 8 km apart. However, when he came to report the time the objects took to pass his timing points, he referred to the last object passing 'the southern most high snow covered crest of Mt. Adams' after 102 s. Now Mt. Adams is some 50 km to the south of his position near Mt. Ranier, and some 80 km from Mt. Ranier. Not only had he reported seeing the objects to the north (to his left) but his statement that the timing points were 8 km apart is irreconcilable with his claim that one of the peaks was Mt. Adams 50 km away to his right. Inexplicably, he also referred twice more to Mt. Adams, albeit in one instance stating that, by that time, the objects were out of his range of vision as far as determining shape and form. In addition, because Mt. Adams rises to 3751 m, nearly 1000 m higher than his flight level, it could not have been one of his timing points; the objects would have been hidden behind it.

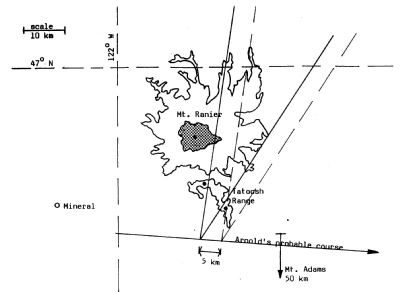

A search of the aeronautical chart covering the area immediately to the south of Mt. Ranier (which does lie 'between Mt. Ranier and Mt. Adams') for a ridge with two peaks 8 km apart shows that the only candidate is the Tatoosh Range, which is marked at one end by Pinnacle Peak (2000 m) and at the other by Lookout (1923 m). The two peaks are almost exactly 8 km apart (see figure 2). Since this range lies directly east of Mineral it must have been the 'ridge' towards which Arnold was flying.

Arnold stated that he had 'two definite points' by which he could time the objects. Later he explained that the two points were the northern and southern crests of a ridge which lay between Mt. Ranier and Mt. Adams and towards which he was flying. On later measurement he found that the two crests (he later called them 'mountains') were 8 km apart. However, when he came to report the time the objects took to pass his timing points, he referred to the last object passing 'the southern most high snow covered crest of Mt. Adams' after 102 s. Now Mt. Adams is some 50 km to the south of his position near Mt. Ranier, and some 80 km from Mt. Ranier. Not only had he reported seeing the objects to the north (to his left) but his statement that the timing points were 8 km apart is irreconcilable with his claim that one of the peaks was Mt. Adams 50 km away to his right. Inexplicably, he also referred twice more to Mt. Adams, albeit in one instance stating that, by that time, the objects were out of his range of vision as far as determining shape and form. In addition, because Mt. Adams rises to 3751 m, nearly 1000 m higher than his flight level, it could not have been one of his timing points; the objects would have been hidden behind it.

A search of the aeronautical chart covering the area immediately to the south of Mt. Ranier (which does lie 'between Mt. Ranier and Mt. Adams') for a ridge with two peaks 8 km apart shows that the only candidate is the Tatoosh Range, which is marked at one end by Pinnacle Peak (2000 m) and at the other by Lookout (1923 m). The two peaks are almost exactly 8 km apart (see figure 2). Since this range lies directly east of Mineral it must have been the 'ridge' towards which Arnold was flying.

Fig 2: Arnold's probable course from Mineral to Yakima near Mt. Ranier, showing the angle subtended by the mirages of nine Cascade peaks and the peaks of the Tatoosh Range used to time their apparent movement. The shaded area of Mt. Ranier is above his stated flight level and should have hidden the mirages unless they were elevated or Arnold was higher than he thought.

It seems that the two peaks of the Tatoosh Range have become confused with Mts. Ranier and Adams, probably very early. In his book, Arnold states that the speed calculation made at Pendleton (2650 km/h) astonished him, and he concluded that the distance measurements were being taken 'far too high up on both Mount Ranier and Mount Adams'. But even taking the distance down to 64 km still produced a speed of 2259 km/h (which he wrongly calculated as 2160 km/h). It is these high speeds that have led to the conclusion by some that the objects were extraterrestrial or alien. Yet in his report to the USAF Arnold had clearly stated that he had timed the objects over a distance of only 8 km.

In his account to Blue Book, Arnold does not give the speed at which he calculated the objects were travelling, nor did he reveal how he had calculated it. However, given a speed of 2160 km/h, a course for the objects of 170º, a minimum distance from Arnold of 40 km and two timing peaks 8 km apart, I constructed figure 3 (q.v.); this may represent the situation as imagined by Arnold. Note that Mt. Adams does not enter into this concept. Now this interpretation is only feasible if Arnold imagined that he was stationary. However he was a moving observer, travelling at between 164 and 180 km/h (the cruising and maximum speeds respectively of his aircraft). Figure 3 demonstrates very clearly that the mysterious objects should have crossed Arnold's course directly in front of him. However he did not report this event. There has to be doubt therefore that Arnold's interpretation of the incident is correct, and I propose to examine another interpretation.

It seems that the two peaks of the Tatoosh Range have become confused with Mts. Ranier and Adams, probably very early. In his book, Arnold states that the speed calculation made at Pendleton (2650 km/h) astonished him, and he concluded that the distance measurements were being taken 'far too high up on both Mount Ranier and Mount Adams'. But even taking the distance down to 64 km still produced a speed of 2259 km/h (which he wrongly calculated as 2160 km/h). It is these high speeds that have led to the conclusion by some that the objects were extraterrestrial or alien. Yet in his report to the USAF Arnold had clearly stated that he had timed the objects over a distance of only 8 km.

In his account to Blue Book, Arnold does not give the speed at which he calculated the objects were travelling, nor did he reveal how he had calculated it. However, given a speed of 2160 km/h, a course for the objects of 170º, a minimum distance from Arnold of 40 km and two timing peaks 8 km apart, I constructed figure 3 (q.v.); this may represent the situation as imagined by Arnold. Note that Mt. Adams does not enter into this concept. Now this interpretation is only feasible if Arnold imagined that he was stationary. However he was a moving observer, travelling at between 164 and 180 km/h (the cruising and maximum speeds respectively of his aircraft). Figure 3 demonstrates very clearly that the mysterious objects should have crossed Arnold's course directly in front of him. However he did not report this event. There has to be doubt therefore that Arnold's interpretation of the incident is correct, and I propose to examine another interpretation.

|

Fig.3

How Arnold may have imagined the strange 'craft' were travelling in relation to his aircraft. Arnold can have had no certain method of determining the course of the objects, but it seems that he deduced it from the graduation in size, the nearest one (apparently) being the largest. The echelon formation, although inverted, must also have given the impression of a southerly course. |

But, if the objects only appeared to be on a southerly course, they can just as well have been flying a parallel course. In that case, the marker peaks in the Tatoosh Range are only 5 km apart (see figure 2). The speed of a very distant object on a parallel course (or any other course for that matter) is very difficult to assess unless one knows what distance it is covering in a given time. All Arnold knew was that the formation took 102 s to pass between his marker peaks (only 5 km apart for a northerly view). If Arnold had calculated the speed that results from covering 5 km in 102 s he would have found that it is 176 km/h, possibly the speed of his own aircraft at the time (which he did not record). This would have alerted him to the possibility that his own movement may have accounted for the apparent movement of the formation. If the formation was very distant it can be regarded as nearly stationary (because of the slow azimuthal change), just as a stationary Moon or planet near the horizon will seem to follow a moving observer. In fact the nine objects could actually have been stationary, but at a great distance. That would explain why they appeared to be fixed together. But what bright stationary objects lay to the north?

What Arnold saw

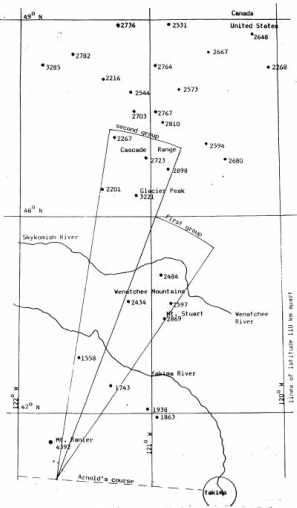

Mt. Ranier is part of the Cascade Range of mountains which extends northward towards the Canadian border 250 km away, and which, as it approaches the border, fans out with a proliferation of high mountains in the height range 2 to 3 km (see figure 4 below).

Fig.4 The Cascade Range, showing the nine peaks that probably caused Arnold's report.

Mt. Stuart, 100 km away in the Wenatchee Mountains, is the start of this chain of peaks. Now Arnold's view northward was across two deep river valleys, that of the Yakima River, about 80 km away, and that of the Skykomish River, about 120 km away. In the calm conditions, it is possible that temperature inversions had formed in either or both of these valleys, so causing mirage effects for anyone viewing objects across them. Arnold can therefore have seen mirages of several of the snow capped Cascade Mountains. They are all more or less permanently covered with snow. Some lower peaks may clear in summer, and this may account for the darker appearance of one object. The blue white colour Arnold saw is consistent with strongly reflected sunlight off snow. It is evident from figure 4 that the first four objects he saw can have been mirages of the four high peaks in the Wenatchee Mountains, 'led' by Mt. Stuart. The second group of five objects can have been mirages of the more distant five mountains around Glacier Peak. They can all have appeared to be flying along the crest of the ridge between Arnold and the Yakima River. The whole group subtends an angle of about 25º in the horizontal plane, and when this angle of view is embraced by the Tatoosh markers it is clear that Arnold must have been 5 km or so south of the direct course from Mineral to Yakima (see figure 2).

Although no specific weather data were given at the time, it has since been alleged that there was a wind from the north or north east and that the air was dry at low elevations with moist air spreading at higher levels. This moist air is likely to have been warmer than the dry air, so forming inversions over the valleys. The usual thin line mirage can have been distorted as the light rays crossed parts of the inversion(s) where the temperature gradient of the thermocline was steep. The mirage of a peak could have appeared to flip and brighten as its light crossed areas of strong refraction and focusing.

It is now evident that Menzel had indeed mentioned the best explanation, albeit as one alternative, in 1963. He even showed an illustration of such mountain top mirages (see figure 5). Unfortunately he did not develop this idea and later appeared to have abandoned it.

Although no specific weather data were given at the time, it has since been alleged that there was a wind from the north or north east and that the air was dry at low elevations with moist air spreading at higher levels. This moist air is likely to have been warmer than the dry air, so forming inversions over the valleys. The usual thin line mirage can have been distorted as the light rays crossed parts of the inversion(s) where the temperature gradient of the thermocline was steep. The mirage of a peak could have appeared to flip and brighten as its light crossed areas of strong refraction and focusing.

It is now evident that Menzel had indeed mentioned the best explanation, albeit as one alternative, in 1963. He even showed an illustration of such mountain top mirages (see figure 5). Unfortunately he did not develop this idea and later appeared to have abandoned it.

Criticism of the mirage hypothesis

In 1968, McDonald made three specific objections to the mirage hypothesis for Arnold's report. These were (1) that the objects changed angular elevation, (2) that they moved through an azimuthal range of about 90º and (3) that they were observed while the observer's own plane was climbing through an altitude interval of between 150 and 300 m. He noted that it was 'utterly unreasonable to claim that such an observation was satisfactorily explained as a mirage'.

McDonald's idea that the objects changed angular elevation seems to be based on Arnold's statement that 'their elevation could have varied a thousand feet [300 m] one way or another up or down...'. McDonald may have confused angular elevation with height elevation; clearly Arnold was referring to the height of the objects, which at their great distance, made little difference to their angular elevation (described by Arnold as practically 0º). In any case Arnold was attempting to assess their flight level, not imply that it varied. McDonald's idea that the objects moved through a horizontal right angle is clearly the result of believing that they were travelling from Mt. Ranier to Mt. Adams. I can find no basis for McDonald's claim that Arnold's aircraft was climbing during the sighting. Arnold himself did not claim this. He set the autopilot for level flight. Evidently all McDonald's objections are based on misunderstandings and his criticism has no force.

To the suggestion that he had seen reflections, 'or even a mirage', Arnold responded that he had observed the objects through an open cockpit window. This deals with internal reflections (and also with raindrops on the window), but it does not counter the mirage hypothesis, which Arnold may not have understood.

It can be objected that Arnold reported seeing the objects outlined 'against the snow' or, as in his book, 'silhouetted against both snow and sky'. There is not enough certainty in this observation for it to have much force. It is not absolutely clear that he was reporting seeing the objects in front of anything but sky.

McDonald's idea that the objects changed angular elevation seems to be based on Arnold's statement that 'their elevation could have varied a thousand feet [300 m] one way or another up or down...'. McDonald may have confused angular elevation with height elevation; clearly Arnold was referring to the height of the objects, which at their great distance, made little difference to their angular elevation (described by Arnold as practically 0º). In any case Arnold was attempting to assess their flight level, not imply that it varied. McDonald's idea that the objects moved through a horizontal right angle is clearly the result of believing that they were travelling from Mt. Ranier to Mt. Adams. I can find no basis for McDonald's claim that Arnold's aircraft was climbing during the sighting. Arnold himself did not claim this. He set the autopilot for level flight. Evidently all McDonald's objections are based on misunderstandings and his criticism has no force.

To the suggestion that he had seen reflections, 'or even a mirage', Arnold responded that he had observed the objects through an open cockpit window. This deals with internal reflections (and also with raindrops on the window), but it does not counter the mirage hypothesis, which Arnold may not have understood.

It can be objected that Arnold reported seeing the objects outlined 'against the snow' or, as in his book, 'silhouetted against both snow and sky'. There is not enough certainty in this observation for it to have much force. It is not absolutely clear that he was reporting seeing the objects in front of anything but sky.

Conclusions

Evidently there is sufficient 'grist' in the report to find an adequate explanation. Indeed it is an explanation already (apparently) adopted by the USAF, but perhaps without justification, and one suggested by Menzel. Arnold saw mirages of nine snow capped peaks of the Cascade Range, although they were between 100 and 200 km away from him. However, because they were so far away they appeared to be travelling over the nearer mountains. His own movement east caused them to appear to move in the same direction, although he interpreted this as a southwards movement because of their graded size and height (both diminishing to the left). He estimated their speed by timing them between two nearby peaks, but his estimate was erroneous because of his wrong assumption about the objects' distance and their (presumed) course. It was also flawed by reason of his own movement. Subsequently his marker peaks were wrongly identified as Mts. Ranier and Adams. The flashes which first attracted his attention were caused by strong focusing of the mirage rays as they crossed parts of the thermocline(s) where the temperature gradients were steep.

It is interesting to note that (in this case) the Mirage Hypothesis explains the large number of objects, their precise number, their appearance in two groups (and the number and disposition in each group), the 'echelon' formation (with the highest to the right), the appearance of being fixed together, the shape of the objects and the reason for the flashes, and the apparent speed of the objects. It would be even more interesting to know what other hypothesis could so comprehensively explain this report. The other explanations proposed are utterly inadequate (and some are downright silly). Even some of Menzel's flew in the face of the facts. Billowing snow would have required a high wind and there was no rain to form raindrops on the windows (Menzel anticipated this objection). On the other hand it was Menzel who first suggested a mirage of mountain peaks, albeit based on an idea previously put forward by Tacker. It is surprising that Menzel did not develop the idea.

The fact that Arnold's report can be explained as a mirage may be significant; many UFO reports may have a similar explanation.

It is interesting to note that (in this case) the Mirage Hypothesis explains the large number of objects, their precise number, their appearance in two groups (and the number and disposition in each group), the 'echelon' formation (with the highest to the right), the appearance of being fixed together, the shape of the objects and the reason for the flashes, and the apparent speed of the objects. It would be even more interesting to know what other hypothesis could so comprehensively explain this report. The other explanations proposed are utterly inadequate (and some are downright silly). Even some of Menzel's flew in the face of the facts. Billowing snow would have required a high wind and there was no rain to form raindrops on the windows (Menzel anticipated this objection). On the other hand it was Menzel who first suggested a mirage of mountain peaks, albeit based on an idea previously put forward by Tacker. It is surprising that Menzel did not develop the idea.

The fact that Arnold's report can be explained as a mirage may be significant; many UFO reports may have a similar explanation.