The origin and purpose of the Pyramids

Why did the ancient Egyptians build pyramidal monuments and what was their purpose? A new hypothesis may offer an explanation.

There are many mysteries concerning the Egyptian pyramids. Why were they built? Who built them? For whom were they built? Why are there more large pyramids from the Fourth Dynasty than the pharaohs who could have been buried in them? Why are all the pyramids empty? Why is the perimeter of the Great Pyramid (Khufu) exactly 2 pi times its height when the ancient Egyptians were ignorant of pi? But there is a more fundamental question: why are the monuments pyramidal?

This last question has not received satisfactory answers, even from Egyptologists. In The Pyramids of Egypt, I E S Edwards suggested that a pyramid represents the slanting rays of the sun and he recorded seeing these rays ‘at about the same angle as the slope of the Great Pyramid’. He found it ‘irresistible’ to conclude that the true pyramid was a means by which the dead king could ascend to heaven. This hypothesis is lent credibility by the Pyramid Texts which speak of the dead king using the rays of the sun as a ramp by which to ascend to the heavens.

Edwards's idea is used to explain the benben, a sacred object in the temple at Heliopolis (‘On’ in the Old Testament), which Edwards states was ‘probably conical’, but which A Fahkry, in his book The Pyramids, describes as ‘pyramidal’. Of course a cone would do just as well to represent sun rays, but the monuments are not conical and it is specious to argue that a pyramid is the nearest the builders could get to a cone. To Fahkry a pyramid is a colossal benben, and so also a sacred object, but this does not explain why the benben itself was pyramidal. Edwards states that the benben was thought to symbolise the primeval mound which was thought to have emerged from primordial waters at the creation of the universe, but this conflicts with the obvious association of the pyramids with a cult of the dead. Fahkry notes that some Egyptologists believe that the development of the pyramid represents simply an architectural evolution, while others see in it the triumph of one religious cult over another. He concluded that ‘there must have been a connection between the pyramidal form and the sun cult’. In a BBC Radio 2 discussion on 16 March 1990, Dr Faruk el Baz suggested that the pyramidal shape was chosen to resist the wind.

It is clear that the pyramid was a revered shape and, as Fahkry has noted, the result of centuries of development and experiment. There is evidence that the more ancient mastaba tombs incorporated a rectangular mound which might well have been pyramidal. Evidently this mound held a spiritual significance, but what is significant about a pyramid?

It is customary to describe the development of the true pyramid from the earlier stepped pyramid, showing how the builders gradually achieved ‘the true pyramid’. But this begs the question of whether or not the builders were aiming at the construction of a true pyramid, and if so why. lf they were aiming at a true pyramid then the stepped pyramid is merely a prototype. In The Riddle of the Pyramids (1974), Kurt Mendelssohn showed that the Meidun pyramid is a true pyramid which collapsed and that the Bent Pyramid at Dahshur was originally intended to be ‘true’. Furthermore, it is known that the inner structure of the true pyramids is practically identical to that of the stepped pyramid. If the builders were, all along, aiming at a true pyramid, why were they doing so?

Edwards notes that in pre-dynastic times the dead were buried in rectangular or oval pits dug in the sand and that the superstructure was unlikely to have consisted of anything more substantial than a heap of sand supported at the sides by a wooden frame. The superstructure of the royal tombs at Abydos, from the reign of Djer onwards, were mounds of sand supported at the sides by walls of mud-brick. The hieroglyph for the Egyptian word for a pyramid (m(e)r) shows a true pyramid supported by such a wall or frame.

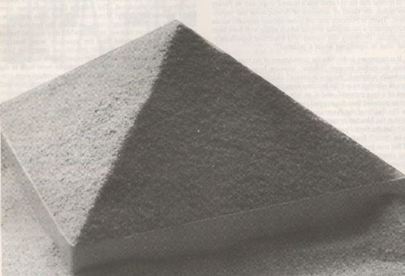

Now if the frame or supporting wall for these heaps was square on plan and if the sand was piled as high as it would go then a pyramid must have emerged (see illustration). On a square base the sand must form a pyramid to reconcile the natural angle of repose formed on each side. I propose that the superstructures of the earliest Egyptian graves were formed in this way and that the Egyptians kept the same form for all subsequent tombs.

This last question has not received satisfactory answers, even from Egyptologists. In The Pyramids of Egypt, I E S Edwards suggested that a pyramid represents the slanting rays of the sun and he recorded seeing these rays ‘at about the same angle as the slope of the Great Pyramid’. He found it ‘irresistible’ to conclude that the true pyramid was a means by which the dead king could ascend to heaven. This hypothesis is lent credibility by the Pyramid Texts which speak of the dead king using the rays of the sun as a ramp by which to ascend to the heavens.

Edwards's idea is used to explain the benben, a sacred object in the temple at Heliopolis (‘On’ in the Old Testament), which Edwards states was ‘probably conical’, but which A Fahkry, in his book The Pyramids, describes as ‘pyramidal’. Of course a cone would do just as well to represent sun rays, but the monuments are not conical and it is specious to argue that a pyramid is the nearest the builders could get to a cone. To Fahkry a pyramid is a colossal benben, and so also a sacred object, but this does not explain why the benben itself was pyramidal. Edwards states that the benben was thought to symbolise the primeval mound which was thought to have emerged from primordial waters at the creation of the universe, but this conflicts with the obvious association of the pyramids with a cult of the dead. Fahkry notes that some Egyptologists believe that the development of the pyramid represents simply an architectural evolution, while others see in it the triumph of one religious cult over another. He concluded that ‘there must have been a connection between the pyramidal form and the sun cult’. In a BBC Radio 2 discussion on 16 March 1990, Dr Faruk el Baz suggested that the pyramidal shape was chosen to resist the wind.

It is clear that the pyramid was a revered shape and, as Fahkry has noted, the result of centuries of development and experiment. There is evidence that the more ancient mastaba tombs incorporated a rectangular mound which might well have been pyramidal. Evidently this mound held a spiritual significance, but what is significant about a pyramid?

It is customary to describe the development of the true pyramid from the earlier stepped pyramid, showing how the builders gradually achieved ‘the true pyramid’. But this begs the question of whether or not the builders were aiming at the construction of a true pyramid, and if so why. lf they were aiming at a true pyramid then the stepped pyramid is merely a prototype. In The Riddle of the Pyramids (1974), Kurt Mendelssohn showed that the Meidun pyramid is a true pyramid which collapsed and that the Bent Pyramid at Dahshur was originally intended to be ‘true’. Furthermore, it is known that the inner structure of the true pyramids is practically identical to that of the stepped pyramid. If the builders were, all along, aiming at a true pyramid, why were they doing so?

Edwards notes that in pre-dynastic times the dead were buried in rectangular or oval pits dug in the sand and that the superstructure was unlikely to have consisted of anything more substantial than a heap of sand supported at the sides by a wooden frame. The superstructure of the royal tombs at Abydos, from the reign of Djer onwards, were mounds of sand supported at the sides by walls of mud-brick. The hieroglyph for the Egyptian word for a pyramid (m(e)r) shows a true pyramid supported by such a wall or frame.

Now if the frame or supporting wall for these heaps was square on plan and if the sand was piled as high as it would go then a pyramid must have emerged (see illustration). On a square base the sand must form a pyramid to reconcile the natural angle of repose formed on each side. I propose that the superstructures of the earliest Egyptian graves were formed in this way and that the Egyptians kept the same form for all subsequent tombs.

We cannot tell whether or not the ancient Egyptians understood why a pyramid must form in such a mound. However, it is reasonable to assume that its persistence caused them to revere it. It can have assumed a sacred significance simply because it was a shape that was always associated with the grave.

A pyramid of sand would not survive for long; wind would soon blow it out of shape, or away altogether. Consequently attempts must have been made to preserve the shape, perhaps by covering it with mud-bricks. Indeed, there is evidence that this was done. Ultimately it must have been decided to preserve the shape in an imperishable form; to build a stone pyramid, a petrification of the sand archetype.

This hypothesis offers a rational explanation for the pyramidal shape. In a desert country what is more natural than that tombs should evolve from a heap of sand? It only needed a square frame to turn such a heap into a pyramid. It is more reasonable to suppose that the Egyptian evolved naturally than that it was invented to represent sun rays.

The purpose of the pyramids

If a pyramidal shape signifies a tomb, then the pyramids are tombs. Indeed it has long been assumed that the pyramids are the tombs of the kings of ancient Egypt, the Pharaohs. Yet there is no evidence that they ever held bodies, although some contain a sarcophagus. The alabaster sarcophagus in the tomb chamber of Sekjemket’s pyramid was sealed, but empty.

The emptiness of the pyramids is usually explained by supposing that either the pyramids were abandoned before burial took place (a specious argument) or that robbers have emptied the contents centuries ago. It is true that there is plenty of evidence that the pyramids were entered, but it does not follow that they were plundered. The robbers themselves may have found the interiors empty. Mendelssohn listed some arguments against the pyramids being tombs, including the fact that some pharaohs built more than one pyramid while they were all buried elsewhere. He suggested that the pyramids were funerary monuments (cenotaphs), built to provide an enterprise large to reform and bind the Egyptians into a unitary state. This begs the question of why the cenotaphs were built in the traditional shape of a tomb and also why sarcophagi were provided. Perhaps the answer to this question has been provided by Alexandre Lenoir. In an article in FMR (‘A dissertation on the pyramids of Egypt’, No. 39, 1989) he boldly claimed that educated travellers and antiquaries are generally in agreement on the nature of the Great Pyramid; ‘all consider it to be the tomb of Osiris’:

So this tomb, dedicated to the Sun, was to receive the supreme God of Egypt when, descending into the lower signs, he deprived nature of his presence; it was therefore his simulacrum, as are all tombs that have been raised in honour of mythological personages...

The official religion of ancient Egypt, including the cult of Osiris, began in the Pyramid Age (2815 to 2294 BC) and it is clear that the pyramids had some religious function. Osiris was god of the dead.

An essential belief of the religion, especially the cult of Osiris, was that man consists of both body and spirit and that the latter lived on after death. Indeed it was believed that one could provide a ‘tomb’ (in effect a cenotaph) for the spirit. Sensuret III, one of the greatest kings of the Middle Kingdom, had a rock cenotaph hewn for himself at Abydos, while his body was buried elsewhere. A cenotaph allowed the spirit of the dead to dwell at Abydos. Similarly the Great Pyramid might have been intended as a dwelling place for the spirit of Osiris. That would explain its emptiness. The emptiness of all the pyramids suggests that they were all intended to host divine spirits. In this way the Egyptian gods dwelt with the people whose gods they were. There is an interesting parallel with the beliefs of the Jews, whose origin may lie in Egypt. They believed that their god, Yahveh, lived first in the empty ark and later in the empty Holy of Holies in Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem.

In this light, the pyramids are not tombs for pharaohs, but tombs for gods. This may explain their huge size and the uniqueness of the Giza group. Only gods could be expected to dwell in such huge tombs. Perhaps the elaborate security measures were not to protect a king’s body and his belongings, but to keep prying humans away from their god; to give him privacy.

Hopeful tomb robbers may have been as disappointed as Pompey when he strode into the Holy of Holies in Jerusalem, looking for Yahveh.

[published in New Humanist, December 1990, Vol. 106, No. 4]

A pyramid of sand would not survive for long; wind would soon blow it out of shape, or away altogether. Consequently attempts must have been made to preserve the shape, perhaps by covering it with mud-bricks. Indeed, there is evidence that this was done. Ultimately it must have been decided to preserve the shape in an imperishable form; to build a stone pyramid, a petrification of the sand archetype.

This hypothesis offers a rational explanation for the pyramidal shape. In a desert country what is more natural than that tombs should evolve from a heap of sand? It only needed a square frame to turn such a heap into a pyramid. It is more reasonable to suppose that the Egyptian evolved naturally than that it was invented to represent sun rays.

The purpose of the pyramids

If a pyramidal shape signifies a tomb, then the pyramids are tombs. Indeed it has long been assumed that the pyramids are the tombs of the kings of ancient Egypt, the Pharaohs. Yet there is no evidence that they ever held bodies, although some contain a sarcophagus. The alabaster sarcophagus in the tomb chamber of Sekjemket’s pyramid was sealed, but empty.

The emptiness of the pyramids is usually explained by supposing that either the pyramids were abandoned before burial took place (a specious argument) or that robbers have emptied the contents centuries ago. It is true that there is plenty of evidence that the pyramids were entered, but it does not follow that they were plundered. The robbers themselves may have found the interiors empty. Mendelssohn listed some arguments against the pyramids being tombs, including the fact that some pharaohs built more than one pyramid while they were all buried elsewhere. He suggested that the pyramids were funerary monuments (cenotaphs), built to provide an enterprise large to reform and bind the Egyptians into a unitary state. This begs the question of why the cenotaphs were built in the traditional shape of a tomb and also why sarcophagi were provided. Perhaps the answer to this question has been provided by Alexandre Lenoir. In an article in FMR (‘A dissertation on the pyramids of Egypt’, No. 39, 1989) he boldly claimed that educated travellers and antiquaries are generally in agreement on the nature of the Great Pyramid; ‘all consider it to be the tomb of Osiris’:

So this tomb, dedicated to the Sun, was to receive the supreme God of Egypt when, descending into the lower signs, he deprived nature of his presence; it was therefore his simulacrum, as are all tombs that have been raised in honour of mythological personages...

The official religion of ancient Egypt, including the cult of Osiris, began in the Pyramid Age (2815 to 2294 BC) and it is clear that the pyramids had some religious function. Osiris was god of the dead.

An essential belief of the religion, especially the cult of Osiris, was that man consists of both body and spirit and that the latter lived on after death. Indeed it was believed that one could provide a ‘tomb’ (in effect a cenotaph) for the spirit. Sensuret III, one of the greatest kings of the Middle Kingdom, had a rock cenotaph hewn for himself at Abydos, while his body was buried elsewhere. A cenotaph allowed the spirit of the dead to dwell at Abydos. Similarly the Great Pyramid might have been intended as a dwelling place for the spirit of Osiris. That would explain its emptiness. The emptiness of all the pyramids suggests that they were all intended to host divine spirits. In this way the Egyptian gods dwelt with the people whose gods they were. There is an interesting parallel with the beliefs of the Jews, whose origin may lie in Egypt. They believed that their god, Yahveh, lived first in the empty ark and later in the empty Holy of Holies in Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem.

In this light, the pyramids are not tombs for pharaohs, but tombs for gods. This may explain their huge size and the uniqueness of the Giza group. Only gods could be expected to dwell in such huge tombs. Perhaps the elaborate security measures were not to protect a king’s body and his belongings, but to keep prying humans away from their god; to give him privacy.

Hopeful tomb robbers may have been as disappointed as Pompey when he strode into the Holy of Holies in Jerusalem, looking for Yahveh.

[published in New Humanist, December 1990, Vol. 106, No. 4]